Could data from retailers, fashion brands and shoppers hold the key to better fitting garments and an end to online shopping disappointments? asks Sarah Krasley

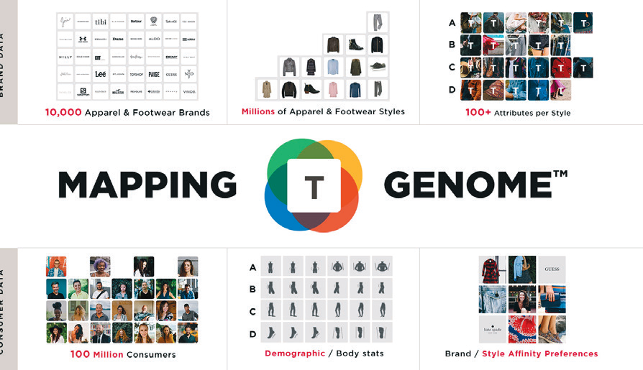

True Fit says its Genome platform offers the largest set of connected fit and style data in the world

The holiday season is here, and my inbox is stuffed with emails from online retailers promising big discounts.

Tempting though these offers may be, shopping online for clothing and footwear continues to pose challenges for many consumers, myself included. Is it really possible to put together a winning ensemble from items you’ve never seen, held or touched – much less worn – in real life?

No wonder some Internet shoppers go to the trouble of purchasing the same item in multiple sizes on their credit cards and then returning to the retailer those sizes that don’t work for them.

We’re also starting to see fashion brands that started life as online-only retailers invest in brick-and-mortar stores that customers can visit to try on an item before they purchase it.

Companies including menswear specialist Bonobos, beauty product company Birchbox and glasses /sunglasses retailer Warby Parker have all set up retail sites where customers have the opportunity to ‘try before they buy’. These stores combine the ease and convenience associated with making an online order, with the customer confidence that comes from having had a real-life, pre-purchase interaction with a product.

The appeal is obvious. For a start, colour, quality of material and finishing details are much easier to assess in real life — but I think the bigger reason why some people are more inclined to make fashion purchases in physical brick-and-mortar stores is that they’re the best places to judge the fit of a garment or a shoe. In other words, there’s nothing like trying something on before you pay for it, in order see how it sits on the unique contours of your body, to see whether it’s flattering or not.

But most retailers cannot afford to open a physical store in every location — and not all customers are able to take a trip to the large cities where these stores tend to spring up.

True Fit is a five-year-old start-up, based in Woburn, Massachusetts, that aims to provide a new answer to this challenge.

Its founders believe that data holds the key to bringing useful insights to three constituents: the shopper who lacks confidence about the potential fit of an online fashion purchase; the retailer, who needs to understand which purchases are kept, which are returned, and why; and the apparel and footwear brand that makes the items in the first place.

True Fit has spent the last five years developing the True Fit Genome, a data set and insights engine that aims to ‘connect the dots’ in order to identify the relationships between millions of shoe and clothing styles from nearly 10,000 brands and nearly 100 million consumers by year end.

All three constituents outlined above in turn participate by contributing data to the platform. Retailers including Macy’s and House of Fraser provide data on what shoppers return. Apparel brands including Clarks, DKNY and Levis provide SKUs [stock keeping units], along with sizing, grading and construction information. And shoppers making online purchases provide feedback on how items fit.

I spoke to Jessica Murphy, co-founder of True Fit, and Chris Moore, the company’s chief analytics officer, about their service.

The end-user generated data, contributed by shoppers, is the category that Chris Moore deems most valuable, as it contains insights about the direct relationship between a garment and an individual.

This description seemed a little vague, so in order to test the service for myself, I created my own True Fit profile, to see how accurately it reflected my experience with a real-life shoe.

True Fit has a partnership with Kate Spade, so I went to KateSpade.com and started digging into my True Fit profile.

Some of the questions were pretty straightforward: I could be pretty certain about the height of my arch, for example.

Others were less so: I was uncertain about whether my calves are narrow, average or full in comparison to other people’s. I also had the option to add fit data from shoes I already own, but none of my best-fitting brands were in the database.

As I moved to the garment section, I found one brand that I had shopped with in the past. Unfortunately, I’ve experienced wide variances in sizing across seasons and garments with this particular brand, so was hard-pressed to answer which of its sizes best correlated to my true size.

I took the experience one step further and went to a Kate Spade store to try on shoes in the sizes that True Fit suggested to me. One pair fit quite well, another did not.

While the data from retailers and brands is likely to be less corrupted by users’ error-prone self-reported fit information, it strikes me that all data must be in good shape in order for the True Fit Genome to function well.

But in fairness, what True Fit is trying to do is really hard and it’s still early days. I may, for example, be an ‘edge case’ who can’t clearly articulate the size of her calves.

The Genome just launched in October and can already boast a pretty impressive set of data from two other sources: retailers and over 10,000 apparel brands. It’s growing very quickly and adding on average 700,000 SKUs per month.

It’s definitely one to watch — but I wouldn’t bet the dress on it just yet.

Sarah Krasley (@sarahkrasley) is the founder and principal of Unreasonable Women , a NYC-based product, service and workplace policy design firm. She is also an Adjunct Professor at New York University’s ITP Program. More about her at sarahkrasley.com

Could better data be a better fit for online clothes buyers?

Default